With more than one-third of the world’s population living in areas at risk for transmission, dengue infection is a leading cause of illness and death in the tropics and subtropics. As many as 100 million people are infected yearly. Dengue is caused by any one of four related viruses transmitted by mosquitoes. There are not yet any vaccines to prevent infection with dengue virus (DENV) and the most effective protective measures are those that avoid mosquito bites. When infected, early recognition and prompt supportive treatment can substantially lower the risk of developing severe disease.

Dengue has emerged as a worldwide problem only since the 1950s. Although dengue rarely occurs in the continental United States, it is endemic in Puerto Rico, and in many popular tourist destinations in Latin America and Southeast Asia; periodic outbreaks occur in Samoa and Guam.

Q.How are dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) spread?

A. Dengue is transmitted to people by the bite of an Aedes mosquito that is infected with a dengue virus. The mosquito becomes infected with dengue virus when it bites a person who has dengue virus in their blood. The person can either have symptoms of dengue fever or DHF, or they may have no symptoms. After about one week, the mosquito can then transmit the virus while biting a healthy person. Dengue cannot be spread directly from person to person.

Q.What are the symptoms of the disease?

A. The principal symptoms of dengue fever are high fever, severe headache, severe pain behind the eyes, joint pain, muscle and bone pain, rash, and mild bleeding (e.g., nose or gums bleed, easy bruising). Generally, younger children and those with their first dengue infection have a milder illness than older children and adults.

Dengue hemorrhagic fever is characterized by a fever that lasts from 2 to 7 days, with general signs and symptoms consistent with dengue fever. When the fever declines, symptoms including persistent vomiting, severe abdominal pain, and difficulty breathing, may develop. This marks the beginning of a 24- to 48-hour period when the smallest blood vessels (capillaries) become excessively permeable (“leaky”), allowing the fluid component to escape from the blood vessels into the peritoneum (causing ascites) and pleural cavity (leading to pleural effusions). This may lead to failure of the circulatory system and shock, followed by death, if circulatory failure is not corrected. In addition, the patient with DHF has a low platelet count and hemorrhagic manifestations, tendency to bruise easily or other types of skin hemorrhages, bleeding nose or gums, and possibly internal bleeding.

Q.What is the treatment for dengue?

A. There is no specific medication for treatment of a dengue infection. Persons who think they have dengue should use analgesics (pain relievers) with acetaminophen and avoid those containing aspirin. They should also rest, drink plenty of fluids, and consult a physician. If they feel worse (e.g., develop vomiting and severe abdominal pain) in the first 24 hours after the fever declines, they should go immediately to the hospital for evaluation.

Q.Is there an effective treatment for dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF)?

A. As with dengue fever, there is no specific medication for DHF. It can however be effectively treated by fluid replacement therapy if an early clinical diagnosis is made. DHF management frequently requires hospitalization. Physicians who suspect that a patient has DHF may want to consult the Dengue Branch at CDC, for more information.

Q. Where can outbreaks of dengue occur?

A.Outbreaks of dengue occur primarily in areas where Ae. aegypti (sometimes also Ae. albopictus) mosquitoes live. This includes most tropical urban areas of the world. Dengue viruses may be introduced into areas by travelers who become infected while visiting other areas of the tropics where dengue commonly exists.

Q.What can be done to reduce the risk of acquiring dengue?

A.There is no vaccine for preventing dengue. The best preventive measure for residents living in areas infested with Ae. aegypti is to eliminate the places where the mosquito lays her eggs, primarily artificial containers that hold water.

Items that collect rainwater or to store water (for example, plastic containers, 55-gallon drums, buckets, or used automobile tires) should be covered or properly discarded. Pet and animal watering containers and vases with fresh flowers should be emptied and cleaned (to remove eggs) at least once a week. This will eliminate the mosquito eggs and larvae and reduce the number of mosquitoes present in these areas.

Using air conditioning or window and door screens reduces the risk of mosquitoes coming indoors. Proper application of mosquito repellents containing 20% to 30% DEET as the active ingredient on exposed skin and clothing decreases the risk of being bitten by mosquitoes. The risk of dengue infection for international travelers appears to be small. There is increased risk if an epidemic is in progress or visitors are in housing without air conditioning or screened windows and doors.

Q.How can we prevent epidemics of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF)?

A.The emphasis for dengue prevention is on sustainable, community-based, integrated mosquito control, with limited reliance on insecticides (chemical larvicides, and adulticides). Preventing epidemic disease requires a coordinated community effort to increase awareness about dengue fever/DHF, how to recognize it, and how to control the mosquito that transmits it. Residents are responsible for keeping their yards and patios free of standing water where mosquitoes can be produced.

Prevention

How to reduce your risk of dengue infection:

There is no vaccine available against dengue, and there are no specific medications to treat a dengue infection. This makes prevention the most important step, and prevention means avoiding mosquito bites if you live in or travel to an endemic area.

The best way to reduce mosquitoes is to eliminate the places where the mosquito lays her eggs, like artificial containers that hold water in and around the home. Outdoors, clean water containers like pet and animal watering containers, flower planter dishes or cover water storage barrels. Look for standing water indoors such as in vases with fresh flowers and clean at least once a week.

The adult mosquitoes like to bite inside as well as around homes, during the day and at night when the lights are on. To protect yourself, use repellent on your skin while indoors or out. When possible, wear long sleeves and pants for additional protection. Also, make sure window and door screens are secure and without holes. If available, use air-conditioning.

If someone in your house is ill with dengue, take extra precautions to prevent mosquitoes from biting the patient and going on to bite others in the household. Sleep under a mosquito bed net, eliminate mosquitoes you find indoors and wear repellent!

Symptoms and What To Do If You Think You Have Dengue

The principal symptoms of dengue are:

High fever and at least two of the following:

Severe headache

Severe eye pain (behind eyes)

Joint pain

Muscle and/or bone pain

Rash

Mild bleeding manifestation (e.g., nose or gum bleed, petechiae, or easy bruising)

Low white cell count

Generally, younger children and those with their first dengue infection have a milder illness than older children and adults.

Watch for warning signs as temperature declines 3 to 7 days after symptoms began.

Go IMMEDIATELY to an emergency room or the closest health care provider if any of the following warning signs appear:

Severe abdominal pain or persistent vomiting

Red spots or patches on the skin

Bleeding from nose or gums

Vomiting blood

Black, tarry stools (feces, excrement)

Drowsiness or irritability

Pale, cold, or clammy skin

Difficulty breathing

Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) is characterized by a fever that lasts from 2 to 7 days, with general signs and symptoms consistent with dengue fever. When the fever declines, warning signs may develop. This marks the beginning of a 24 to 48 hour period when the smallest blood vessels (capillaries) become excessively permeable (“leaky”), allowing the fluid component to escape from the blood vessels into the peritoneum (causing ascites) and pleural cavity (leading to pleural effusions). This may lead to failure of the circulatory system and shock, and possibly death without prompt, appropriate treatment. In addition, the patient with DHF has a low platelet count and hemorrhagic manifestations, tendency to bruise easily or have other types of skin hemorrhages, bleeding nose or gums, and possibly internal bleeding.

Treatment

There is no specific medication for treatment of a dengue infection. Persons who think they have dengue should use analgesics (pain relievers) with acetaminophen and avoid those containing ibuprofen, Naproxen, aspirin or aspirin containing drugs. They should also rest, drink plenty of fluids to prevent dehydration, avoid mosquito bites while febrile and consult a physician.

As with dengue, there is no specific medication for DHF. If a clinical diagnosis is made early, a health care provider can effectively treat DHF using fluid replacement therapy. Adequately management of DHF generally requires hospitalization.

Epidemiology

Dengue fever (DF) is caused by any of four closely related viruses, or serotypes: dengue 1-4. Infection with one serotype does not protect against the others, and sequential infections put people at greater risk for dengue hemorraghic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS).

Transmission of the Dengue Virus

Dengue is transmitted between people by the mosquitoesAedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, which are found throughout the world. Insects that transmit disease are vectors. Symptoms of infection usually begin 4 - 7 days after the mosquito bite and typically last 3 - 10 days. In order for transmission to occur the mosquito must feed on a person during a 5- day period when large amounts of virus are in the blood; this period usually begins a little before the person become symptomatic. Some people never have significant symptoms but can still infect mosquitoes. After entering the mosquito in the blood meal, the virus will require an additional 8-12 days incubation before it can then be transmitted to another human. The mosquito remains infected for the remainder of its life, which might be days or a few weeks.

In rare cases dengue can be transmitted in organ transplants or blood transfusions from infected donors, and there is evidence of transmission from an infected pregnant mother to her fetus. But in the vast majority of infections, a mosquito bite is responsible.

In many parts of the tropics and subtropics, dengue is endemic, that is, it occurs every year, usually during a season when Aedes mosquito populations are high, often when rainfall is optimal for breeding. These areas are, however, additionally at periodic risk for epidemic dengue, when large numbers of people become infected during a short period. Dengue epidemics require a coincidence of large numbers of vector mosquitoes, large numbers of people with no immunity to one of the four virus types (DENV 1, DENV 2, DENV 3, DENV 4), and the opportunity for contact between the two. Although Aedes are common in the southern U. S., dengue is endemic in northern Mexico, and the U.S. population has no immunity, the lack of dengue transmission in the continental U.S. is primarily because contact between people and the vectors is too infrequent to sustain transmission.

Dengue is an Emerging Disease

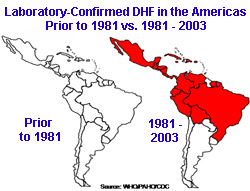

The four dengue viruses originated in monkeys and independently jumped to humans in Africa or Southeast Asia between 100 and 800 years ago. Dengue remained a relatively minor, geographically restricted disease until the middle of the 20th century. The disruption of the second world war – in particular the coincidental transport of Aedes mosquitoes around the world in cargo - are thought to have played a crucial role in the dissemination of the viruses. DHF was first documented only in the 1950s during epidemics in the Philippines and Thailand. It was not until 1981 that large numbers of DHF cases began to appear in the Carribean and Latin America, where highly effective Aedes control programs had been in place until the early 1970s.

Global Dengue

Today about 2.5 billion people, or 40% of the world’s population, live in areas where there is a risk of dengue transmission see WHO/Impact of Dengue. Dengue is endemic in at least 100 countries in Asia, the Pacific, the Americas, Africa, and the Caribbean. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 50 to 100 million infections occur yearly, including 500,000 DHF cases and 22,000 deaths, mostly among children.

Dengue in the United States

Nearly all dengue cases reported in the 48 continental states were acquired elsewhere by travelers or immigrants. (Travel Associated Dengue Infections - United States, 2001- 2004 ,Imported Dengue - United States, 1999 and 2000 ) Because contact between Aedes and people is infrequent in the continental U.S., these imported cases rarely result in secondary transmission. The last reported continental dengue outbreak was in south Texas in 2005. (Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever - U.S.- Mexico Border, 2005) A small dengue outbreak occurred in Hawaii in 2001.

Most dengue cases in U.S. citizens occur in those inhabitants of Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Samoa and Guam, which are endemic for the virus. Dengue and DHF have been a particular challenge in Puerto Rico, where outbreaks have been reported since 1915 and large island-wide epidemics have been documented since the late 1960s. The most recent island-wide epidemic occurred in 2007, when more than 10,000 cases were diagnosed. In Puerto Rico, and most of the Caribbean Basin, the principle dengue vector Ae. aegypti is abundant year-round. Dengue transmission in the Puerto Rico follows a seasonal pattern. Low transmission season begins in March and lasts until June, and high transmission begins in August until November.

Dengue Surveillance in the U.S.

DF and DHF cases have long been reportable by law to public health authorities in 26 states. Beginning in 2009, all nationally diagnosed dengue infections will be reportable to the CDC.

Statistics on cases have been compiled in Puerto Rico since 1915 and, since 1969, CDC’s Dengue Branch, located at San Juan, has operated the island-wide passive dengue surveillance system (PDSS) in partnership with the Puerto Rico Department of Health. PDSS was instrumental in confirming the endemic presence of dengue transmission in Puerto Rico, identifying the first case of DHF in the Americas, and detecting the first cluster of cases of DHF and the first laboratory-confirmed, dengue-related death in Puerto Rico. Instructions and forms for reporting suspected or confirmed cases of dengue are linked below.

Entomology & Ecology

Aedes aegypti, the principal mosquito vector of dengue viruses is an insect closely associated with humans and their dwellings. People not only provide the mosquitoes with blood meals but also water-holding containers in and around the home needed to complete their development. The mosquito lays her eggs on the sides of containers with water and eggs hatch into larvae after a rain or flooding. A larva changes into a pupa in about a week and into a mosquito in two days. See Aedes main aquatic habitats; from tree cavities to toilets and learn about the mosquitoes life cycle. People also furnish shelter as Ae. aegypti preferentially rests in darker cool areas, such as closets leading to their ability to bite indoors.

It is very difficult to control or eliminate Ae. aegypti mosquitoes because they have adaptations to the environment that make them highly resilient, or with the ability to rapidly bounce back to initial numbers after disturbances resulting from natural phenomena (e.g., droughts) or human interventions (e.g., control measures). One such adaptation is the ability of the eggs to withstand desiccation (drying) and to survive without water for several months on the inner walls of containers. For example, if we were to eliminate all larvae, pupae, and adult Ae. aegypti at once from a site, its population could recover two weeks later as a result of egg hatching following rainfall or the addition of water to containers harboring eggs.

It is likely that Ae.aegypti is continually responding or adapting to environmental change. For example, it was recently found that Ae. aegypti is able to undergo immature development in broken or open septic tanks [PDF - 1 page] in Puerto Rico, resulting in the production of hundreds or thousands of Ae.aegypti adults per day. In general, it is expected that control interventions will change the spatial and temporal dispersal of Ae. aegypti and perhaps the pattern of habitat utilization. For these reasons, entomological studies should be included to give support before and throughout vector control operations.